You qualify for Medicaid in Michigan with a household income up to the following limits (the eligibility calculations include a built-in 5% income disregard, which are included in these limits):

While these are the main groups covered by Medicaid, coverage is also available for certain low-income people who are 65 or older, disabled, or blind. But for these populations there are asset limits as well as income limits. See the Department of Community Health website for more information on covered groups and eligibility guidelines.

Federal poverty level calculatorof Federal Poverty Level

Apply online using MI Bridges. Fill out form DCH-1426. Call the application help line at 1-855-276-4627.

Eligibility: Children up to 1 year with household income up to 195% of FPL. Children ages 1-18 with household income up to 160% of FPL; children with household income up to 212% of FPL qualify for MICHILD (low-cost health insurance for kids). Pregnant women with household income up to 195% of FPL. Adults with household income up to 133% of FPL (138% with the built-in income disregard). Select other groups: see details

Yes, Michigan’s Medicaid expansion program, which is called Healthy Michigan, took effect in April 2014, a few months after Medicaid expansion began in many other states.

Former Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, a Republican, pushed for an alternative approach to Medicaid expansion in Michigan and ultimately gained bipartisan support for Healthy Michigan, albeit with a start date of April 2014 instead of January 2014. Adults under age 65 are eligible for Healthy Michigan with incomes up to 138% of the poverty level (as called for in the ACA), but the state obtained approval from the Obama administration to charge premiums equal to 2% of income for people with income above the poverty level. The money was held in health savings accounts (MI Health Account, or MIHA) administered by the state and Michigan was one of three states that continued to collect Medicaid premiums during the COVID public health emergency. However, the last MI Health Account payments were due in January 2024, and the state is no longer collecting these fees from Healthy Michigan enrollees with income above the poverty level. 1

We created this guide to help you choose the right health insurance plan right for you and your family. An ACA Marketplace plan may be a good choice for many consumers, and we will guide you through the options.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Michigan.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Michigan as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Here is how you can apply for Medicaid coverage in Michigan:

Apply online using MI Bridges (if you are any age), or begin the process through Healthcare.gov, and you’ll be directed to Michigan Medicaid (use this option only if you are under age 65, and don’t have Medicare).

Fill out a paper application (the form is DCH-1426) and turn it in at a local office, by fax, or by mail. The mailing address is:

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Health Insurance Affordability Program

PO Box 8123

Royal Oak, MI 48068-9985

Find the location or fax number for a local office.

Get help with your application by calling the application help line at 1-855-276-4627.

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive assistance through Medicaid with the cost of Medicare premiums, cost sharing, and services Medicare doesn’t cover — such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare beneficiaries in Michigan explains these benefits, including Medicare Savings Programs, Extra Help, long-term care benefits, and income guidelines for assistance.

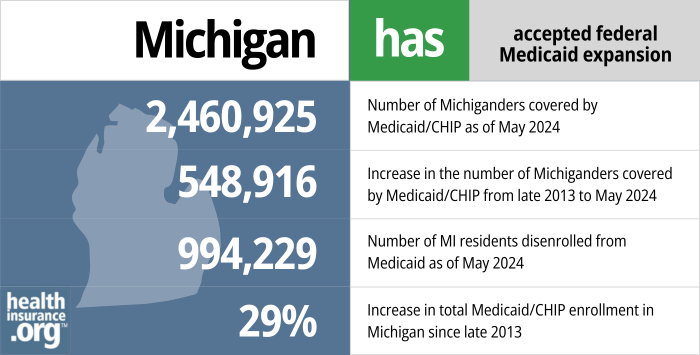

From March 2020 through March 2023, states could not disenroll anyone from Medicaid, even if they no longer met the eligibility guidelines (there were exceptions if the person passed away, moved out of state, or requested a coverage termination). But that rule ended March 31, 2023, and states could resume disenrollments as early as April 1.

Michigan began the year-long “unwinding” of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule in May 2023, and the first round of disenrollments in Michigan came at the end of June 2023.

By March 2024, more than 883,000 people had been disenrolled from Michigan Medicaid. 5 As has been the case in most states, the majority of the disenrollments were procedural, meaning the state didn’t have enough information to determine whether the person was still eligible. 6

People who lose their Medicaid coverage have access to a special enrollment period during which they can transition to other coverage (Medicare, an employer’s plan, or individual/family health coverage). Those who aren’t eligible for an employer’s plan or Medicare will be able to obtain their own individual/family health coverage via HealthCare.gov, which is the exchange/marketplace in Michigan. There’s an extended special enrollment period, through November 30, 2024, for people who lose Medicaid to transition to a plan through HealthCare.gov. 7 But it’s important to sign up before the date that Medicaid ends, to avoid a gap in coverage (Marketplace coverage is not retroactive, so it won’t take effect until the first of the month after the enrollment is submitted).

Total Medicaid enrollment in Michigan stood at more than 3 million people by late 2022, including Healthy Michigan (Medicaid expansion) enrollees as well as the traditionally eligible Medicaid population. By February 2023, nearly a year into the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule, total enrollment in Michigan Medicaid/CHIP was 2,652,901. 8

As of April 2023, there were more than a million people enrolled in Healthy Michigan, but that had dropped to 728,350 by June 2024. 9

Enrollment in Healthy Michigan had been under 652,000 people at the start of 2020. But enrollment climbed significantly during the COVID pandemic, due in large part to the ban on Medicaid disenrollments that was in effect nationwide from March 2020 through March 2023. It started to decline after disenrollments resumed, and with the unwinding process nearly complete, it had dropped to under 729,000 people.

No, Michigan does not currently have a work requirement for Medicaid enrollees. Michigan did briefly implement a work requirement for the Healthy Michigan (Medicaid expansion) population, but it was only used for a couple of months in early 2020.

You can read more details below, but Michigan’s short-lived Medicaid work requirement was based on legislation the state enacted in 2018 and received federal approval in late 2018. The work requirement took effect in January 2020, requiring non-exempt Medicaid expansion enrollees to complete at least 80 hours per month of activities that could include work, school, job training, etc. The enrollees had to begin reporting their work hours as of February 2020.

But in early March, a federal judge overturned the state’s work requirement, which immediately eliminated the work requirement and reporting requirements (the lawsuit had been filed in November 2019 in an effort to block the work requirement). Gov. Gretchen Whitmer — who has long opposed the Medicaid work requirement but who took office after it had been enshrined in statute and approved by CMS — had asked Michigan lawmakers to delay implementation of the Medicaid work requirement until the lawsuit was resolved, in order to avoid wasting taxpayer dollars. But they opted to allow it to continue as planned, although that only lasted a couple of months.

Utah and Michigan were the only states with Medicaid work requirements in effect as of early 2020, and both were soon suspended (Michigan’s by a court ruling, and Utah’s in response to the COVID-19 pandemic). Medicaid work requirements had been approved in several other states as well, but some were overturned by lawsuits, and others were suspended or postponed by the state due to COVID. By 2021, the Biden administration had revoked work requirement waivers in every state where they had previously been approved, including Michigan.

If the work requirement had remained in place in Michigan, the number of people covered under Healthy Michigan was expected to decline, but that’s a feature, not a bug: The reduction in enrollment is a key element of Medicaid work requirements, and Governor Snyder noted when he signed the legislation that Healthy Michigan enrollment was far higher than had been predicted.

Part of the Healthy Michigan Medicaid expansion included a requirement that enrollees with income above the federal poverty level pay premiums equal to 2% of their income. The money was held in health savings accounts (MI Health Account, or MIHA) administered by the state. Although people were not disenrolled if they didn’t pay the MI Health Account fees, state tax refunds and lottery winnings were garnished if outstanding fees were owed.

Michigan was one of three states that continued to collect Medicaid premiums during the COVID public health emergency. But the state stopped requiring the MI Health Account fees to be paid in January 2024. 1

Healthy Michigan enrollees could reduce their MIHA fees with certain healthy behaviors, including “completing an annual Healthy Michigan Plan health risk assessment and agreeing to stay healthy or work on getting healthier.” But the Healthy Behaviors Requirement was also discontinued as of January 2024. 1

The Michigan legislature approved a Medicaid work requirement during the 2018 session (the version that passed is summarized here; the modifications created by 2019’s SB362 — described below — are here). Although the work requirement was overturned by a judge and approval was subsequently revoked by the Biden administration, the following is a summary of how it would have worked if it had been allowed to remain in place:

Enrollees could be non-compliant (either not working or not reporting their work to the state) for up to three months in a 12-month period, but after that, they would lose eligibility for Medicaid for at least a month and wouldn’t have been able to re-enroll without becoming compliant with the work requirement.

SB897 passed the Senate in April 2018, almost entirely along party lines (all Democrats in the Senate voted no, as did one Republican, Senator Margaret O’Brien; the remaining Republicans all voted yes). The measure passed the House in June (again, almost entirely along party lines — one Republican joined Democrats in voting against it, while the other 61 Republicans all voted in favor of imposing a work requirement for Medicaid). Although Governor Snyder had opposed some provisions in the Senate’s version of the bill, he signed the final version of the bill into law in June 2018.

The next step was for the state to seek federal approval for the work requirement. The waiver proposal was submitted to CMS in September 2018 and federal approval was granted just a few months later, in December 2018. The Trump Administration had already approved work requirements in five other states by that point (Kentucky, Arkansas, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Indiana), and approved Maine’s work requirement waiver on the same day Michigan’s was approved. (Maine’s waiver proposal was created entirely by the LePage administration, without legislation backing it. So new Governor Janet Mills was able to simply withdraw the proposal after taking office, and a work requirement will not take effect in Maine; Gov. Whitmer did not have the same leeway in Michigan, as the work requirement was in statute.)

Michigan’s legislation initially called for non-exempt individuals to work at least 29 hours per week in order to be eligible for continued Medicaid coverage, but that was later amended to 80 hours per month, which was more in line with what other states had proposed. The Senate bill also would have exempted people in counties where unemployment exceeded 8.5%. But that provision was controversial, as it essentially would have exempted rural areas (with predominantly white populations) but not urban areas like Flint and Detroit (with people of color making up a larger percentage of the population) because although there are pockets of high unemployment, they don’t extend to the entire county. That provision was also scrapped in the version of the bill that was sent to Gov. Snyder.

Various populations would have been exempt from the work requirement, including those with disabilities, the medically frail, people under 19 (under 21 if a former foster care youth) or over age 62, pregnant women, full-time students, people who are caretakers of a child under six or an incapacitated person who needs full-time care (only one adult per household can be exempt as a caretaker), and people receiving unemployment benefits or recently released from incarceration.

The fiscal note for SB897 provides rough estimates of the number of people expected to be exempt. The work requirement would have applied to an estimated 670,000 non-disabled Healthy Michigan (Medicaid expansion) enrollees. An estimated 130,000 of them would have been exempt, with the other 540,000 having to comply with the work requirement.

The majority of non-disabled Medicaid recipients are already working or attending school, but the House fiscal analysis projected that enrollment in Healthy Michigan would have declined by somewhere between 5% and 10% as a result of the work requirement. Loss of access to Medicaid could be due to increased income that makes a person ineligible for Medicaid, or failure to comply with the work requirement or the reporting requirements that go along with the work requirement (as noted below, the relaxed reporting requirements included in SB362 were expected to reduce the number of people who would lose coverage, but only slightly).

The fiscal note estimated that after the work requirement was fully implemented and the upfront costs were completed, the work requirement could save the state of Michigan between $5 million and $20 million per year. This would have been due to the reduction in enrollment in Healthy Michigan, which is ultimately the goal of Medicaid work requirements. As Michigan Senate Minority Leader, Jim Ananich (D, Flint) has said, if the goal were to boost employment, “we’d put money toward daycare, we’d put money toward transportation, we’d make sure the talent programs we’re talking about funding were already in place.” But instead, the goal was a reduction in the number of people covered by Medicaid expansion, and a work requirement is an effective way to do that. It also makes it easy to blame the loss of coverage on the individuals themselves (i.e., they should have gotten a job) rather than addressing things like intergenerational poverty.

SB362, which Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed into law in September 2019, made some changes to the impending work requirement in an effort to reduce the number of people who would inadvertently lose coverage under the program. The new legislation gave people until the last day of a month to report work hours for the previous month (as opposed to only until the 10th day of the month to report work activities from the previous month, as the original legislation required), and it also essentially gave people an extra 60 days to report compliance (after missing the reporting deadline) without the month in question being considered a non-compliance month. SB362 also exempted people from having to report their work hours if the state can verify their work activity “through other data available to the department.”

According to a fiscal analysis of SB362, the legislation was likely to reduce the number of people who will lose coverage under the work requirements (projected at 27,000 to 54,000 people), but only “minimally.”

And the GOP-led legislature eliminated a provision in Whitmer’s proposed budget that would have provided $10 million for the state to use for outreach and education about the new work requirement, and to help people comply with it. Consumer advocates noted that although SB362 would help to make compliance with the work requirement easier than it would otherwise have been, it’s still almost certain to lead to inadvertent coverage losses (among people who are working but aren’t aware of the reporting requirements or aren’t able to fulfill them), especially without the “work supports” funding that lawmakers removed from the proposed budget.

In a letter to lawmakers, Whitmer called Michigan’s work requirement “the most onerous in the nation” and reiterated her concerns about the coverage losses that were likely to result from the program. Once it was clear that lawmakers would not approve the $10 million that Whitmer had proposed to fund a public information campaign and compliance assistance related to the work requirement, Whitmer noted that “it now appears that the legislature is less interested in giving Michiganders the facts and the tools to comply with work requirements than in taking away Michiganders’ health insurance.” She urged lawmakers to reconsider the outreach funding, and to also consider a provision that would automatically terminate the work requirement if it becomes clear that a significant number of people are losing coverage.

The Healthy Michigan work requirement was ultimately overturned by a judge and revoked by the Biden administration. But SB362 remains in place and would apply if the work requirement were to be resurrected in the future.

In December 2015, CMS approved Michigan’s second waiver, albeit an adjusted form of the waiver that the state had submitted. The legislation Michigan had passed called for changes to Medicaid eligibility after an enrollee had been in the program for 48 cumulative months. Michigan’s plan was to have individuals at that point either switch to a QHP through the exchange (subsidized with Medicaid funds), or remain in the Healthy Michigan Plan but with cost-sharing of up to 7% of income (with an opportunity to reduce the cost-sharing by participating in various healthy behaviors).

Some of this (the 7% of income cost-sharing, and the 48-month time limit) presented problems for the Obama administration CMS, but the waiver had to be approved in order to keep the Healthy Michigan program active past April 2016, as the stipulations had been built into the state law.

So CMS worked with Michigan officials to reach a compromise: As of April 1, 2018 (four years after Healthy Michigan took effect), some Healthy Michigan enrollees with income above the poverty level (ie, between 100% and 138% of the poverty level) had to either switch to a QHP subsidized with Medicaid funds, or work with their doctors to fulfill the healthy behavior requirements to remain on the Healthy Michigan Plan.

This change applied to people who had been enrolled in Healthy Michigan for 12 or more consecutive months. And there was no longer a mention of cost-sharing amounting to 7% of income, but there was still an opportunity for enrollees to reduce their cost-sharing via healthy behaviors. It should be noted, however, that about 80% of Healthy Michigan enrollees have income below the poverty level, and the second waiver makes no changes to their coverage under the program.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.